An anthropologist and archaeologist have called bullshit on the centuries-old story of human civilization, and it could change what you think is possible in modern politics and society. The Dawn of Everything challenges the pastiness of prehistory with recent archeological and ethnographic evidence to reveal a grossly misrepresented yet playful history of large scale prehistoric societies that experimented over thousands of years (with and without agriculture) and left behind monumental architecture without evidence of kings or ruling classes.

The traditional story went like this: In the beginning human civilizations were small, simple, and egalitarian, but with the rise of farming our trajectory shifted inescapably towards large, complex, and increasingly hierarchical cities and eventually the nation-state. We are told the rise of human civilization as we know it today could have only resulted from the seemingly inevitable and linear shift to agriculture—from “primitive” egalitarian societies in a distinct line of progress towards “advanced” kingdoms with the rigid class structures that we all recognize today.

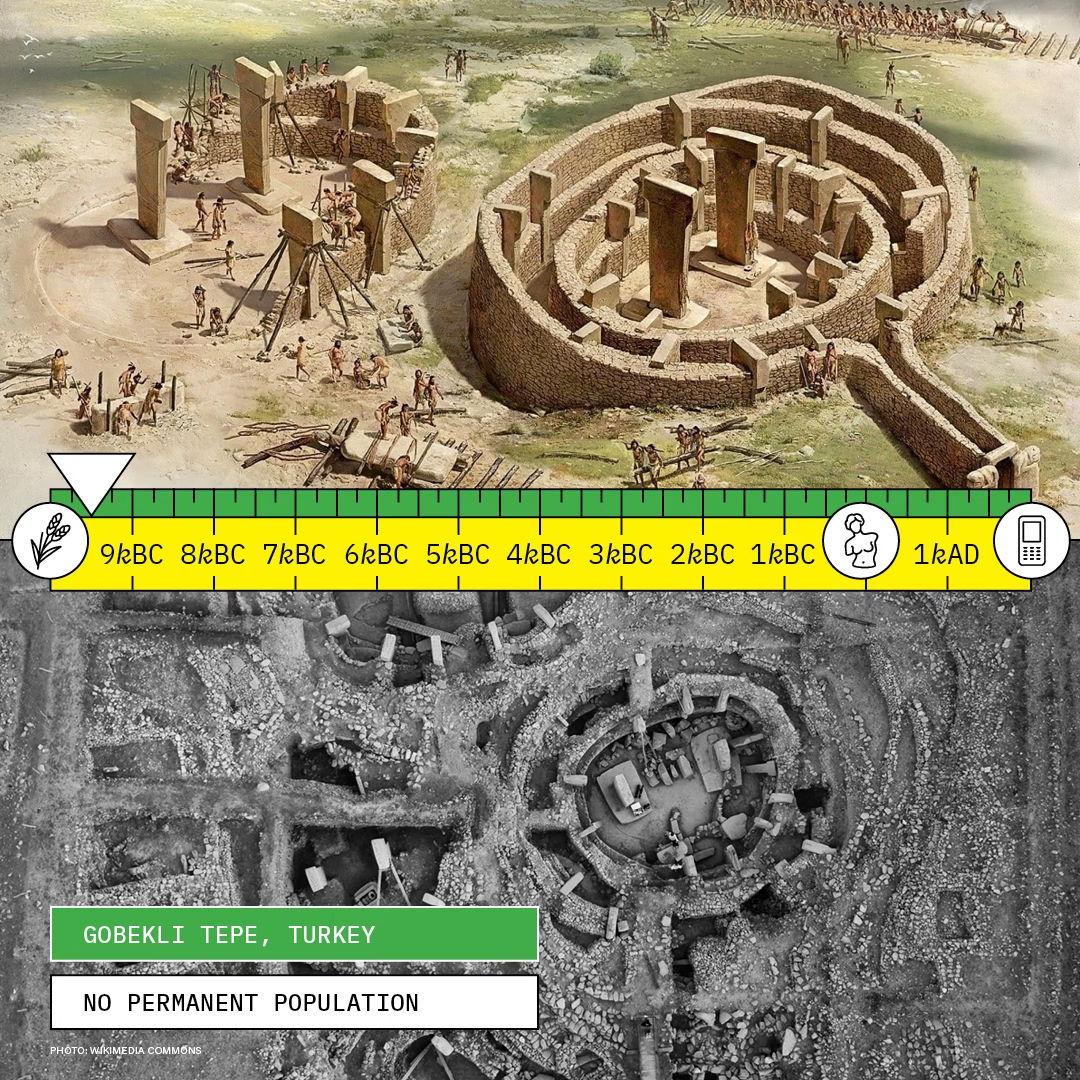

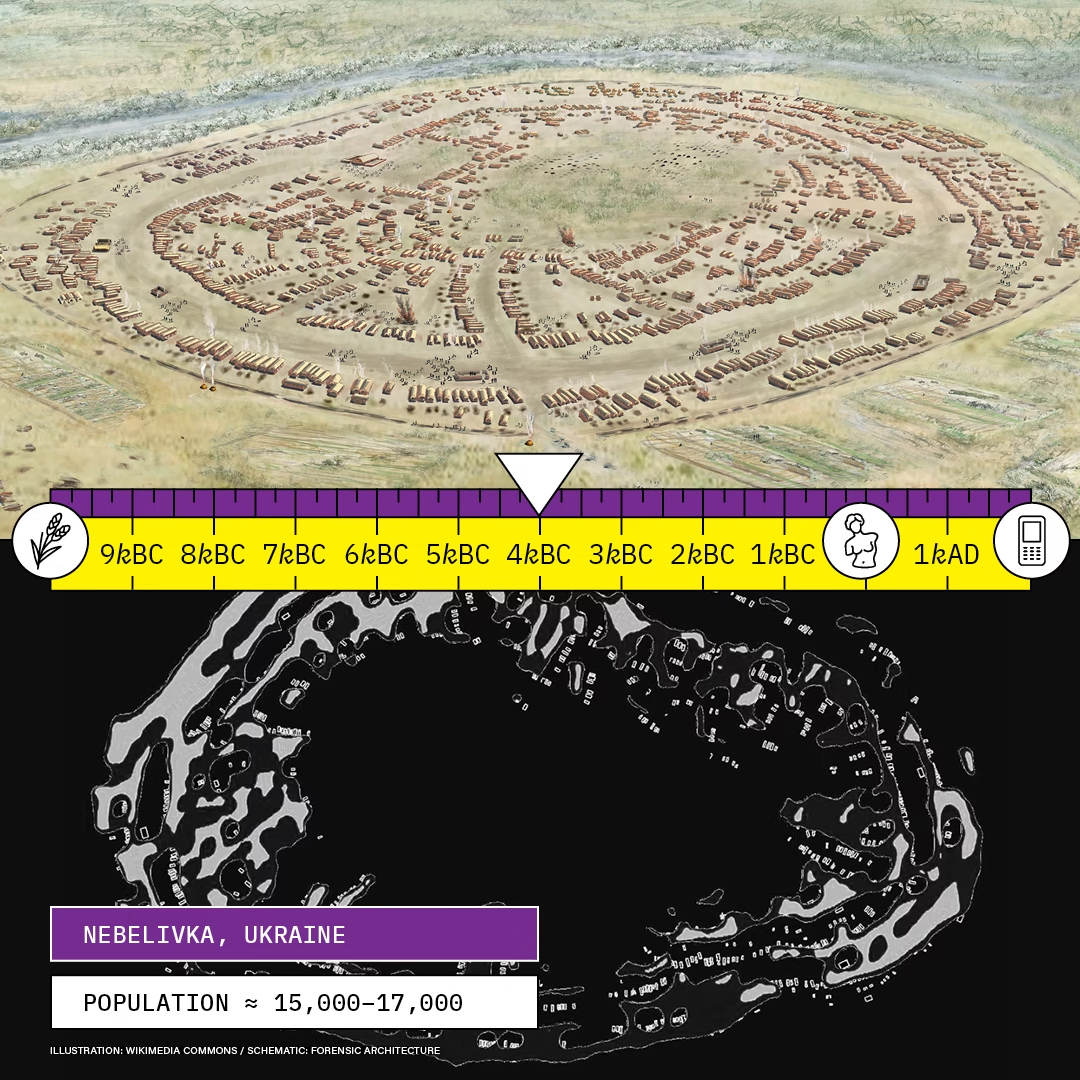

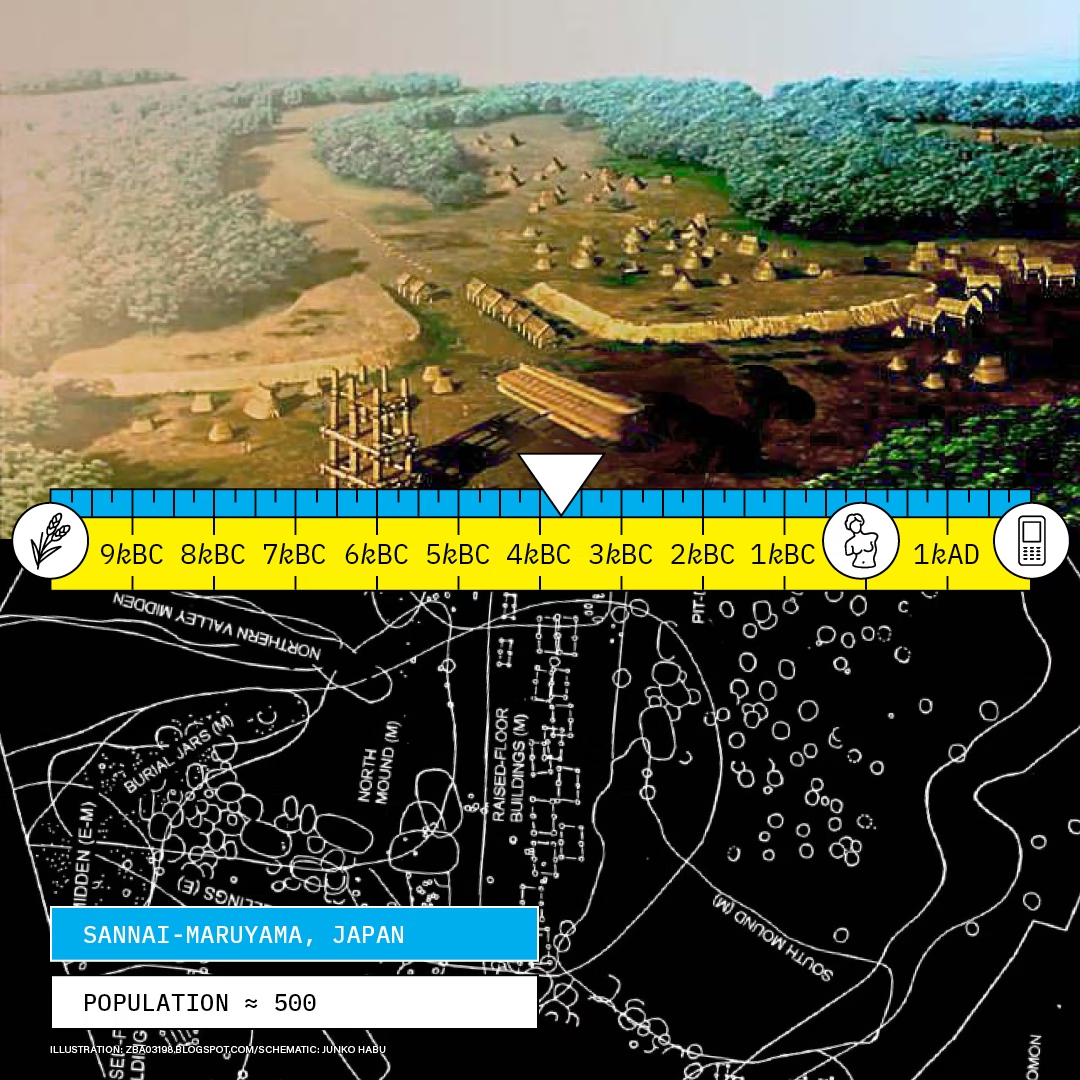

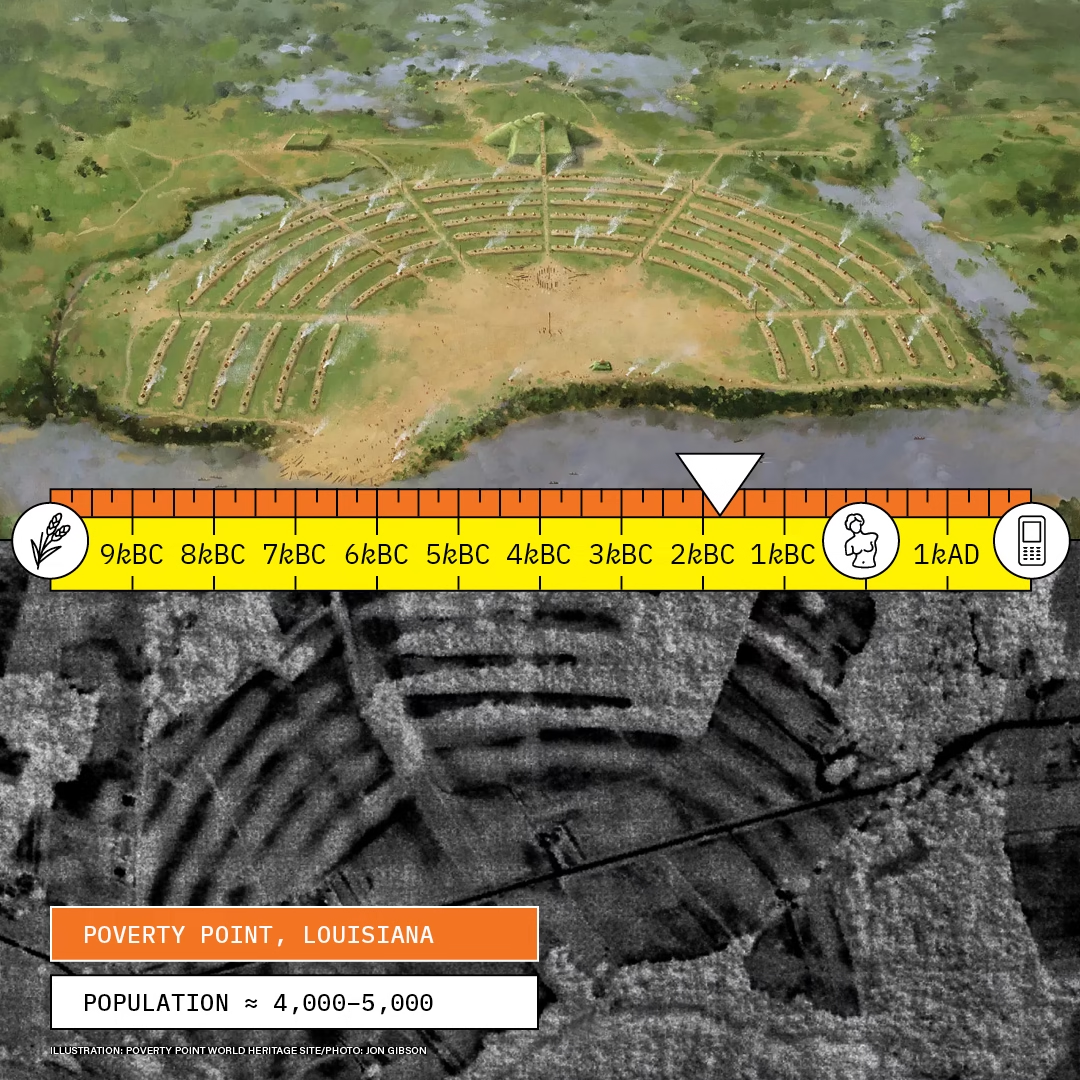

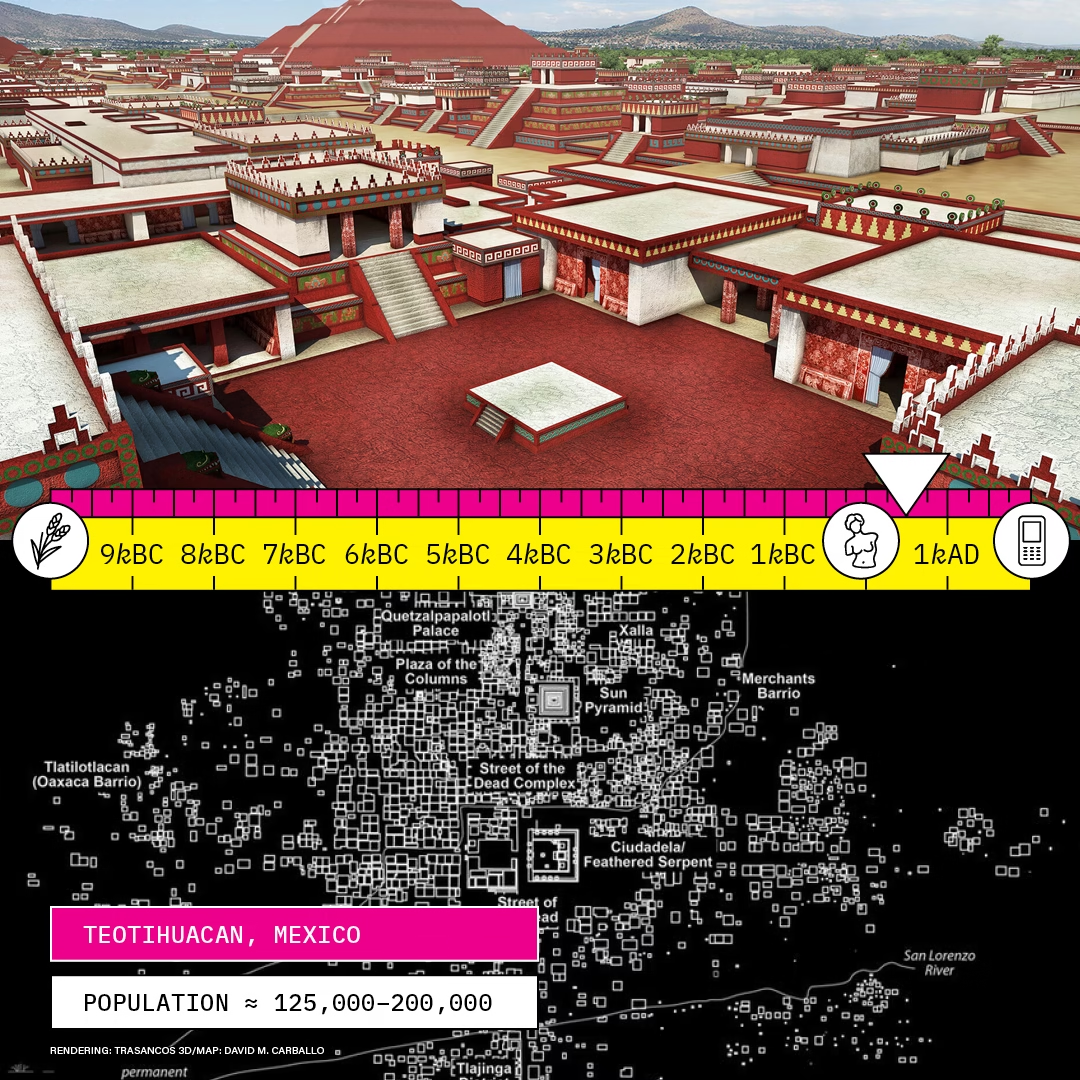

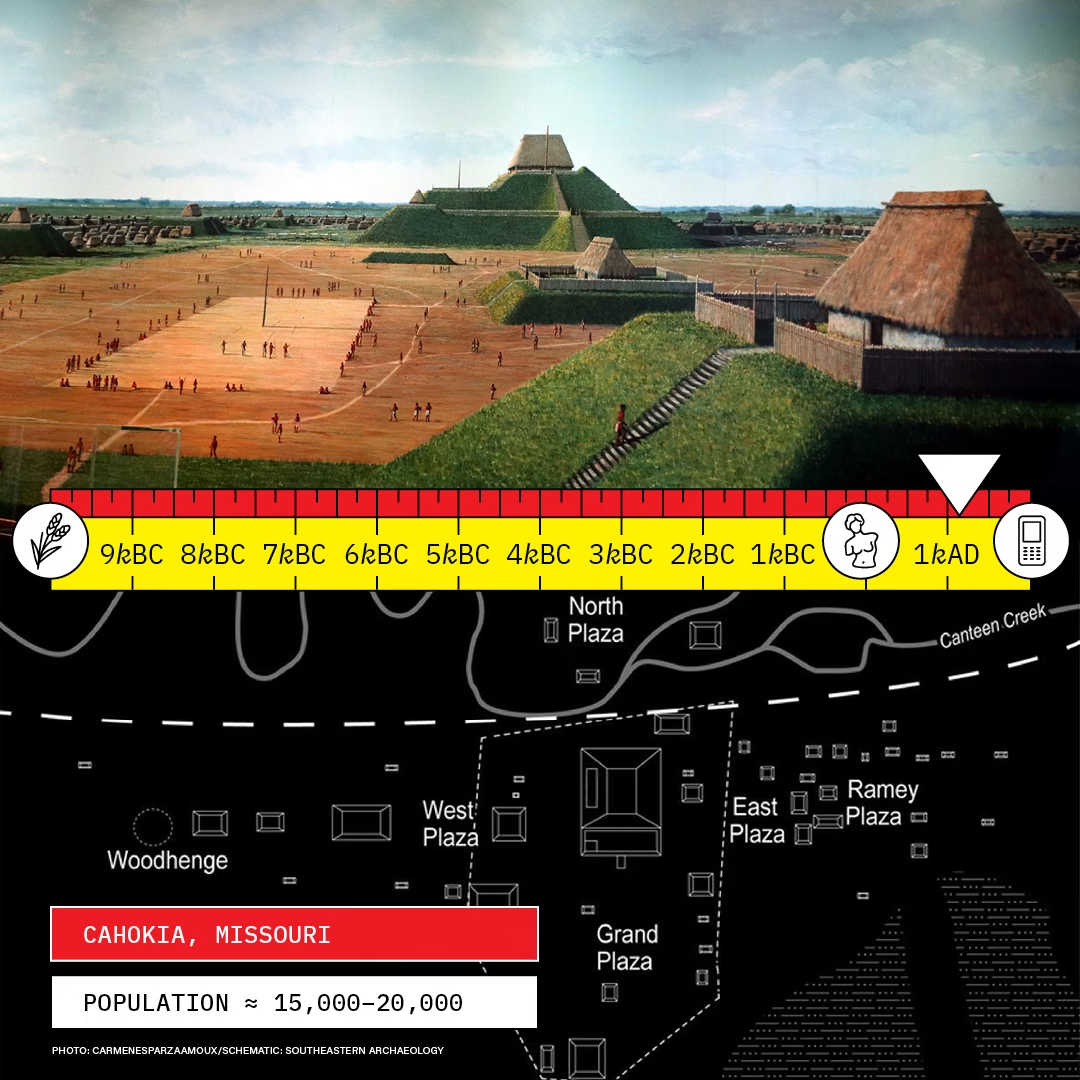

In their 2021 book, The Dawn of Everything, David Wengrow and David Graeber meticulously deconstruct more than 800 pages of late archeological and ethnographic evidence to uncover a story of civilization that looks nothing like the traditional narrative we have been told for more than a quarter millennium. The authors show that large prehistoric populations experimented with a range of social and political systems regardless of agriculture, even rotating seasonally between social arrangements, and leaving behind monumental architecture but no evidence of ruling elites.

Long before democracy in ancient Greece, we see evidence of large cities across the world without kings or ruling classes. This evidence gives a very different picture of agriculture as a conscious experiment, often adopted partially by prehistoric people over the course of thousands of years, rather than a sudden, inevitable outcome of social evolution. The authors argue it is modern peoples who appear to have entered a political and social dark age, where experimentation with political and social forms of organization have been lost to a false sense of determinism under the nation state.

So how did this story get lost, and how did we arrive at our modern notion of social evolution? For answers, the authors take us back to a well documented series of encounters between indigenous peoples and early European colonists who were confronted with numerous revolutionary customs among the large, indigenous, and egalitarian societies of the Great Lakes. Among other things, these peoples of the “New World” exposed European colonists to the smoking of tobacco, the drinking of caffeinated beverages, and the functioning of large scale democratic societies for the first time.

Kondiaronk, a renowned Wendat-Huron statesman, orator, and indigenous philosopher was often invited to dine and debate with the colonial French Governor-General, Frontenac, and these conversations were recorded in Baron de Lahontan’s 1703 account New Voyages to North America, which widely circulated in numerous languages throughout Europe for more than a century. This indigenous critique found a broad European readership precisely because it presented surprising and unprecedented ideas to pre-enlightenment Europeans who were yet to embark on the Age of Reason.

This indigenous critique had an enormous impact on European sensibilities. Just about every major French enlightenment thinker from Montesquieu to Voltaire embraced themes directly from Kandioronk and other “savage critics” featured in colonist travel accounts. These ideas would underpin the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau who described himself as an avid reader of colonial travelogues that fomented political debate in France in the early 1700s. His essays on the origins of the state are regarded as inspirational texts for the French revolution and crucial in the formation of leftist political thought.

In response to the dangerous implications of these ideas and the revolution it had helped inspire, conservative thinkers turned this indigenous critique on its head, laying the basis for our linear understanding of social evolution. Writers and thinkers such as Lord Kames, Adam Furgeson, John Millar, and Adam Smith invented a counter argument, a theory breaking social progress down into distinct stages (four to be exact) based entirely on subsistence practices—not happiness or human freedom as Kandioronk had eloquently argued.

The new paradigm of so called “conjectural history" effectively responded to the indigenous critique by focusing our attention instead on concepts of property accumulation and technological progress, giving us the lasting misconception that all arrangements in society are determined by economic imperatives. It also explained away European’s social and political subordination to kings and ruling elites as a symptom of their progress and a prerequisite for modern civilization as we know it. This had a profound effect on how indigenous people were imagined by Europeans and how they viewed themselves.

With evidence, we now know prehistoric people were not primitive beings, politically or socially. There were no distinct stages of human progress defined by farming methods or subsistence practices. People thousands of years ago were like people today, far more complicated and creative than the categories attempting to define us would admit. However, we are beginning to understand that prehistoric people engaged more freely in social and political experimentation than we do today, some living in populations of tens of thousands but without the assumption that the ways of organizing society were fixed in time.

For Graeber and Wengrow, the question we must ask ourselves now is how did we get stuck? Why do we still believe that inequality is inevitable and irreversible in human civilization? Why do we believe a story that tells us shitty relationships of power are the price of air-conditioning, stocked shelves, and social progress—the so-called “Faustian bargain.” The Dawn of Everything calls bullshit on more than 300 years of false narrative that is still with us to this day, and it reminds us that our story may have been far more interesting than we imagined, and our future still unwritten.